May has delivered us into June. Three weeks beyond that exchange, the solstice will pass and spring will give way to summer.

Months and seasons are always on the move, relentlessly carrying us along on the steady current of time’s eternal flow.

Moreover, from the moment of the solstice’s passing, our daily light allotment will thereafter begin to dwindle, diminishing incrementally as we head toward winter’s darkness.

Seems impossible, right?

We’ve barely tasted spring. Many seeds and plants still need getting into the ground. Birds are yet on the nest. Local bluegill are just beginning to spawn.

Yet, here we are—close enough to look out yonder and see the year’s halfway point coming up the vernal hill and heading our way!

A few mornings ago I stood on the cottage deck, watching the river. Though still early, temperatures were already nearing the 70-degree mark, with forecasters claiming we’d hit 80˚F.

Muggy air carried the sweet scent of honeysuckle. And from somewhere high in the greening sycamores, a Baltimore oriole was whistling his tune.

This is a good vantage point for checking out the pool below — especially before the sun climbs high enough to shine directly onto the surface. I sometimes spot smallmouth feeding along the swirling edge where fast water from the riffle above pours into the slack.

Yet this time, it wasn’t a fish in the stream that caught my eye, rather a bunch of insects clinging to the limestone blocks forming our cottage’s exterior wall. Mayflies, large ones — dozens, hundreds, possibly thousands! A sight which, like the morning sun, immediately warmed this aging trout bum’s heart.

Whenever I see them, I’m momentarily transported back to my favorite north country trout waters. To a trout-besotted fly fisherman, mayflies are practically as important as the fish itself.

Most fish, from catfish to bass, will eat mayflies. However, mayflies are a trout’s cornerstone food source. And the art and history of fly fishing for trout is largely predicated upon offering a bit of fakery to the fish that emulates one stage or another of these insects.

For centuries, avid trout anglers — using bits of fur, feather, and other materials attached to tiny hooks — have been “tying” and employing literally thousands of different mayfly-imitating patterns, hoping to fool fish.

Mayflies emerge regularly from our “cottage pool” on the Stillwater during warmer months, often hatching at twilight or during the night. Hatches can number in the thousands of insects — which are greedily scarfed up by bats, swallows, or cedar waxwings, and equally relished by the fish and minnows, crayfish, bullfrogs, and queen snakes who also call the pool home.

My mayfly identification skills are a bit rusty. But considering the slow current, warm water, and partially mucky bottom make-up of the pool, along with the insect’s two-inch length — not counting the trio of extending tails, or cerci — I suspect they were a species of Hexagenia.

Mayflies are aquatic insects. Ninety-nine-plus percent of their life, starting from a tiny egg, is lived underwater as a nymph — more properly, a naiad — in the silt and muck of a stream’s bottom, or else clinging to the underside of a submerged rock or log. There they remain and grow for a period of one or two years, rarely three.

Then mayflies do something so wondrous it’s almost magical.

The grown naiads swim to the surface, split, and emerge from their ugly nymphal skins, subsequently changing into functionally winged, air-breathing insects. Exquisitely beautiful bugs, some of us would insist. They have only vestigial mouth parts, and can neither feed nor bite.

After a period of rest, the mayfly molts one final time — an act unique among all insects. Afterwards, they mate. New eggs are deposited into the water moments later.

Then the winged adults die.

That’s the mayfly’s lot. A year or two as an ugly nymph in the dark underwater muck, a rush into the sunlight of a warm green world, a dance in the sky, and a procreative moment — followed by sudden death. A story of such heartbreaking brevity it’s become a poignant metaphor for our own fleeting life.

Even the mayfly’s scientific classification echoes this ephemeral nature: of the Order Ephemeroptera (Mayflies), from the Greek ephemeros… “for a day; short-lived,” plus pteron “wing.” Winged adults whose lives are brief.

Yorkshire poet Alan Hartley, in his “Sonnet to a Mayfly,” says this: “Throughout long years I’ve sought to find my way. You found fulfillment in a single day.”

Isn’t that a nice change of view, a worthwhile lesson from the poet’s perspective?

The ephemeral is everywhere in life and nature — from the fleeting existence of mayflies to the passing of months and seasons. Yet seed and stone, water and wine, all find their moment in the fabric of time.

Amid the ephemeral lies both hope and magic.

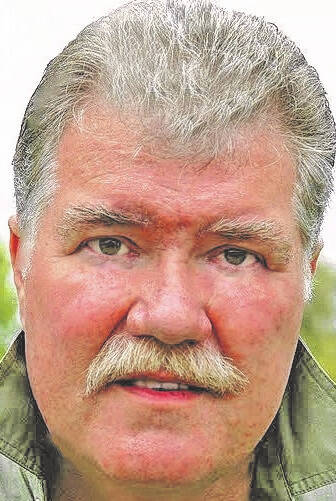

Reach Jim McGuire at [email protected].