Daddy longlegs, or harvestmen, aren’t spiders. Let’s clear that up straight away.

While both are members of the Arachnida class of joint-legged invertebrates, harvestmen and spiders are separated into different orders: spiders in Araneae and daddy longlegs are Opilione.

This isn’t just a case of classification hair-splitting, either. On an entomological basis, a daddy longlegs is surprisingly more closely related to ticks and mites.

I actually grew up calling them granddaddies or granddaddy longlegs — but never once heard them referred to as harvestmen, or to my recollection, the foreshortened daddy longlegs. Everyone I knew, family and friends, just called them grandaddies.

For me, a curious personal oddity was the fact their cursory eight-legged spidery look never once triggered my acute arachnophobia, which, true spider or not, I would have logically expected.

I guess granddaddies just seemed more interesting or weird than scary. I’m left with a puzzle yet to be satisfactorily solved.

Should you ever really examine a granddaddy closely, you’re apt to conclude the creature might have sprung from the imagination of H.G. Wells, a science fiction creature come to life!

A granddaddy’s body is small and oval — head, thorax, and abdomen fused into one. Look closely and you’ll note a sort of topside turret with a single pair of tiny eyes.

Their most obvious feature, of course, is their namesake’s long and delicate legs. Each leg sports seven segments and curves out at the “foot” tip. If our legs were proportionally as long, they’d measure upwards of fifty feet!

Should a leg get detached, it can continue twitching on its own for some time. Some think this is a defense for distracting a possible predator. Furthermore, that lost leg can be regrown — generally at the time of molting.

Granddaddies molt about every week-and-a-half until they’re mature. The torso skin splits, the upsized new body emerges, and long legs are pulled free one at a time, like shucking out of a pants leg. The whole process takes perhaps 20 minutes.

A granddaddy uses his legs not only for mobility — including walking on water — but also as shock absorbers. Watch close — even when hustling along, a granddaddy’s body stays on level keel.

The second pair of legs, the longest, are employed as “feelers,” or antennae, sensing devices that constantly check things ahead, touching, examining, alerting to food or warning of danger.

Regarding food, the harvestman is an omnivore and eats a wide variety of plant matter, fungi, and organic material from other creatures — living and dead — plus any small insects, including spiders, they catch. After a meal, the granddaddy will carefully clean its legs by drawing them, one at a time, through its mandibles.

As summer progresses you’ll likely begin to notice these long-legged spider-like creatures everywhere — clinging to walls, tree trunks, porch posts and fence rails, the lid of the barbecue, wandering around the yard, or crossing a woodland trail.

So, is such sudden conspicuous abundance evidence of a granddaddy longlegs boom?

Probably not. Late summer is simply when our granddaddy population matures. Since a big granddaddy, measured across his long, spindly legs, can top six inches, they’re just more noticeable and thus more likely to catch our eye.

Incidentally, you might occasionally hear talk of how granddaddy longlegs are extremely poisonous, and the only thing saving us from being fatally bitten is the fangs being too short to penetrate our skin.

This is a myth. An old wives’ tale equally repeated by old husbands, and not infrequently by teachers and outdoor folks who should know better.

In truth, a daddy longlegs or harvestman, has no poison glands and produces no venom. They can’t bite — and except for emitting a whiff of smelly scent should you hold one too tight, they’re perfectly harmless.

Along those same lines, in case you’re still thinking “spider,” granddaddies possess no silk glands and can’t build webs.

During the summer mating season, female harvestmen or granddaddies (yes, they are properly called “harvestmen” or daddy longlegs) deposit fertilized eggs into crevices and cracks, tree holes, and the underside of buildings. Come winter, all the adults will die.

By the way, should a granddaddy find its way into your house, folklore warns that it’s bad luck to kill the wanderer. I always comply by carefully catching the offending fellow (male fellow or female fellow) and relocating him/her to a more appropriate setting outdoors.

My mother, who was raised on a farm in eastern Kentucky, often told how she and her siblings would employ a granddaddy’s help to locate lost stock.

“We’d bend close to that ol’ granddaddy and say, ‘Granddaddy, granddaddy, where is the cow?’ He’d lift one of those long legs, wave it around, point one direction or t’other… and off us youngin’s would go.”

“Did you always find the cows?” I’d ask.

Mom would nod. “Usually,” she’d say, then grin. “Course even for a wise ol’ granddaddy, a lost cow can prove mighty elusive.”

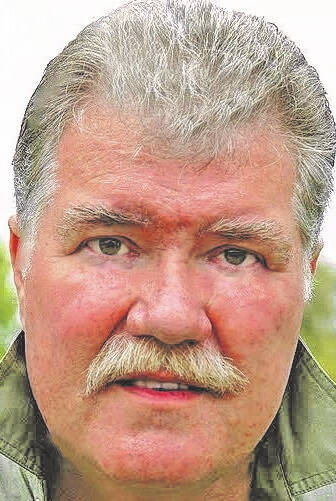

Reach Jim McGuire at [email protected].