“Thank goodness for this January Thaw!” the senior sharing the hardware store’s aisle proclaimed. “Don’t think I could have taken much more of that dang cold!”

We were browsing the chainsaw parts and accessories section for needed items.

He was looking for some sort of filter. He kept pulling little packages off their hooks, turning them over, adjusting his glasses with a quick thumb-poke, trying to read the packet’s fine print.

Being a senior myself, I was doing pretty much the same—searching for a replacement chain. But I’d forgotten and left my readers in the car; however, my product packages, and their print, were bigger.

As we continued to pluck and squint, sorting our way through possibilities, we talked about weather, our firewood-making struggles, and shared feelings of urgency about getting back to our respective woodpiles.

Mid-January had been making outdoor work tough by meting out a two-week dose of arctic cold. Deep, penetrating cold that numbs the very marrow in your bones; a brutal cold that keeps you inside, hunkered close to the woodstove and listening to wind moaning around eaves, as more and more of the river freezes over.

You burn firewood at an excessive rate and eventually get to worrying whether your firewood supply will outlast the harsh spell of weather.

Thankfully, January finally relented, offering blessed relief by serving up a much-needed thaw.

Like Indian Summer or Blackberry Winter, the January Thaw is one of those regularly occurring weather events those who pay attention to seasonal vagaries recognize and expect.

Some years a January Thaw only lasts a few days; or it might hang around a couple of weeks. Yet once the thaw ends, winter returns—perhaps in full force, though possibly in a milder form lacking any real teeth. You can’t, however, predict or count on this more merciful version.

I wanted to work while I could without suffering in dire cold.

“I was always told to make hay while the sun shines,” I said, “except now it’s firewood and unseasonable warmth.”

“You can’t ever trust Ohio’s weather,” my fellow shopper agreed. “A January Thaw might last… or could change tomorrow. I don’t want to be sawing wood in sleet, snow, rain, or the freezing cold!”

“Me neither,” I said—and followed up with a victorious “Ah-ha!” whoop when I realized I’d found a chain to fit my saw.

Earlier that morning, as I was cutting my way through a foot-thick osage orange log, I’d sawed into something metal. Very big and very hard. It felt and sounded like either steel or iron!

The day was cloudy and damp, the ground muddy from recent rains. But it was also blessedly mild, with afternoon highs predicted to climb into the upper forties. A wonderful change from the days of single-digit temperatures we’d endured.

A tree-cutting friend had delivered a fresh batch of logs a few days earlier. I started to work right after breakfast, figuring to saw up sufficient rounds to split into a couple of cords—enough firewood to do us into March.

Then the chainsaw bucked and screeched! I yanked it up and hit the kill bar! And in the sudden aftermath silence, I examined both the damage and source.

When you heat with wood and saw your cordwood from logs supplied by a tree-service cutter, rusty nails or bits of old fencewire are pretty common. After all, these logs often come from trees cut along overgrown fencelines, or backyards and similar residential property situations rather than a forest or farm woodlot. Trees in such places get regularly used for makeshift posts, tool racks, swing and hammock hangers, playground gyms, and occasionally as the aerial foundation for a treehouse.

You gotta expect to find various left-behind bits and pieces of their former double-duty lives. As best I can before I begin sawing the log into 18-20 inch rounds for subsequent splitting into stovewood lengths, I inspect every portion—especially the closest-to-the-stump sections.

Indeed, I’d given this log a careful scrutiny. However, no amount of painstaking examination, short of using a metal detector, would have revealed a hint of the hazard buried deep in the log’s interior.

My saw chain was now ruined—dulled beyond repair. I had to use hand tools to dig my way into the log, and it took a lot of chopping and digging to figure out what I’d encountered.

Osage orange—or if you prefer, hedge apple or horse apple—is hard, dense, tough wood. Though it burns hot and well, it will also shoot out a spray of sparks when you open a stove’s door and provide a bit more draft and a gulp of fresh oxygen. Despite this, I like having some of it in my firewood mix, but you have to be mindful and cautious if you don’t relish abrupt fiery showers.

Once I’d opened that section of osage log, I discovered I’d sawn into a 6-inch long railroad spike!

The hefty chunk of serious, unforgiving metal was almost smack in the tree’s center. But not, as you might expect, situated crossways, as it would have been if pounded in; instead, it was aligned lengthways with the log. The growing tree had simply swallowed and surrounded the steel spike.

Obviously, it was a vintage iron spike—a near-indestructible hunk of railroading history that would think nothing of spending a century or two encased in a tree.

Not much can damage such a spike! No wonder my chainsaw had kicked and howled.

I did a little kicking and howling myself since the saw chain it had so promptly destroyed was only weeks old—and a premium one, at that. I’d ordered it online and it cost more than I’d paid for the wood.

Thoughts of ordering a second pricey chain online, and possibly losing that one, too, to another bit of buried metal somewhere in another log in the same woodpile, were simply unacceptable to a frugal Irishman.

Besides, I wanted to renew my ready-to-burn firewood supply as quickly as possible while the milder mid-winter thaw days continued. Starting today!

Hence the trip to the hardware store. And why I’m now playing catch-up around scheduled appointments and obligations, as I try to beat winter’s weather’s possible vagaries.

Oh, yeah—I also bought two saw chains…just in case.

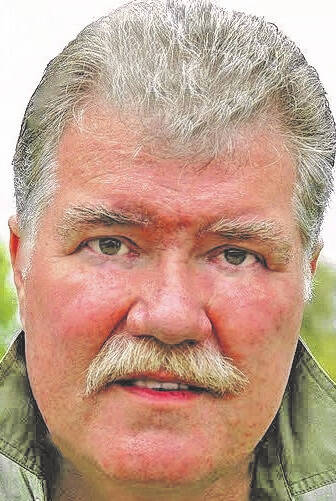

Reach Jim McGuire at [email protected].