The night was soft and sultry.

Daisy the dog and I were out for our usual pre-bedtime reconnoiter.

All was peaceful and quiet.

Not a sound could be heard. Neither the slightest velvety whisper of a single breeze-rustled leaf amid summer’s lush canopy nor the least murmur of water seeking its way over stones in the nearby Stillwater River slipping endlessly along on its eternal journey.

Even the subliminal background prattle of frogs and crickets was missing—as if even these nighttime choristers had all gone collectively mute.

A wonderment of diamond-bright stars spattered the darkened sky, accompanied by the pearlescent glow of a waning Sturgeon Moon just rising to find its way across.

It was a relaxed, welcoming night that felt as if the whole world had kicked back in an easy chair and put its feet up, comfortably settled in for a bit of a rest.

I was standing near the tangle of bushy cedars, giving the dog her space and time, when a brief yellow glimmer caught my peripheral vision. I swiveled around for a better view.

There, from just above the long grass bordering the board fence, the bright flash came again—familiar, unmistakable.

Lightning bug!

And just that quick, my heart was gladdened as the years fell away while my thoughts were flooded with sweet recollections of childhood summer evenings spent chasing fireflies.

Mom and Dad would sit on the porch and watch as I stalked my way around the backyard in fervent pursuit, chasing those tiny flashing lights.

One by one I would gently catch the slow-whirring bugs and put them into my favorite lightning bug jars—tall, skinny glass containers which originally came packed with olives from the local A&P grocery store on West Third Street.

My father had previously poked holes in the jar’s lids. And I’d likely have added a sprig of green limb with an intact leaf or two from the porch-side haw tree.

By the end of the evening’s antics, my jars would be full. I’d take them to my room, place them on the nightstand beside my bed, and fall happily asleep to the winking and blinking of my unfortunate captives.

Survivors were turned loose in the morning.

Decades later, the sight of any lightning bug still provides a direct link to that idyllic past. Which is why I was so delighted upon seeing those recent fireflies.

Regardless of whether you call them lightning bugs or fireflies, these harmless insects have been enchanting folks for centuries. Even though, scientifically speaking, they’re neither flies nor true bugs.

Fireflies are actually winged beetles, belonging to the family Lampyridae. Worldwide, there are over 2000 species of fireflies. They can be found on every continent except Antarctica.

Entomologists have cataloged more than 200 species of fireflies in North America. Most are found only in the eastern half of the country.

And while experts seem to differ on exactly how many species of fireflies are in Ohio, seeing as how Indiana counts more than forty, it’s likely we, too, host several dozen.

The firefly’s light is accomplished through a chemical reaction. Luciferin is combined with an enzyme called Lucifrease, plus adenosine triphosphate (ATP), and oxygen.

The result is natural light, or to give it its fancy term, bioluminescence.

Though the bioillumination process is fairly understood, scientists are still debating how the little beetles turn their nightlights on and off.

Firefly light is “cool” in that it produces almost no heat. It is also highly efficient. Almost 100 percent of a firefly’s bioluminescence energy is given off as light. By comparison, an electric bulb wastes 90 percent of its energy as heat, with only 10 percent being turned into light.

Fireflies in their larval stage are called “glowworms.” Remember that old Mills Brothers song? But while all glowworms glow—or bioluminesce—not all adult fireflies flash. Perhaps 20 percent of the species found locally are non-flashers, while in the western states, almost all fireflies are flashless.

Of course, the whole impetus behind a firefly’s flash can be summed up in one word—sex. Or if you prefer, procreation.

Male fireflies, operating under the philosophy that it pays to advertise, flash to find a mate. These flashes are distinctive in their pattern from species to species.

When the female, who is coyly ensconced in the grass, sees the winking taillight of a prospective mate, she shows interest with a flash of her own. The male flies closer and signals again. Milady reciprocates. And thus a firefly romance is kindled, one alternating flash after another.

Except sometimes the flasher in the grass turns out to be not an available lass from the assumed tribe, but a predatory female of an entirely different species who has learned to mimic the correct flash patterns. When she lures the poor lust-addled male to her boudoir, his embarrassment is mercifully brief because this beckoning harpy promptly kills and eats him.

Some experts think firefly numbers are in decline. I hope they’re wrong. Fireflies possess a whimsical magic we all need a dose of from time to time. It would be no small tragedy to lose these little twinklers.

Without my beloved lightning bugs, summer nights would be both lonely and dark.

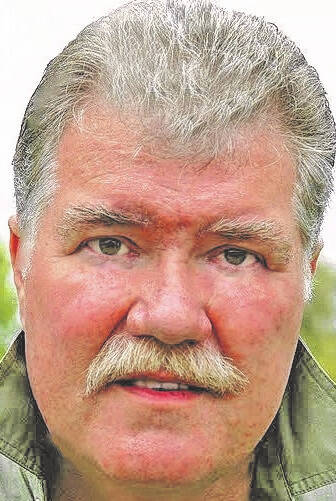

Reach Jim McGuire at [email protected].