August is headed for the exit door—summer’s final full month making its last hurrah.

The month’s final days reveal a season on the cusp of change. A landscape neither altogether summer nor quite yet autumn, but a bit of both—like the blurred mix of colors on a spinning pinwheel.

Goldenrod, ironweed, cardinal flower, Jerusalem artichoke, blazing star, Joe Pye weed, sunflowers, forget-me-not. Perhaps New England asters and fringed gentian. Mostly yellow and gold and purple blooms. Plants you’ll still find blooming well into September and even beyond.

Splashes of bright color that act as a counterpoint to the patchwork of early-changing leaves. And make no mistake, there are a few gaudy hunts and intimations of those Technicolor days ahead. Just the other day, I came across a large trailside sassafras. A big percentage of its many leaves were already various hues of scarlet and crimson.

These last-of-summer days dawn misty and damp, as the sun takes its time rising. There’s often a tang in the air which seems a mix of dust and dry grass, but also cider and woodsmoke.

Fox grapes hang in purple pods along the river. Hickory leaves are beginning to rust.

Katydids call in the earlier dark, causing us to once again remember that old country proverb as to how six weeks from hearing late summer’s first katydid, we’ll see our first frost.

Late summer is a season of prophecy and fulfillment—of promises already kept and promises now being made.

The kitchen table fairly creaks under the weight of the garden’s bounty. Sweet corn, tomatoes, squash, beans, onions, carrots, peppers, melons, new potatoes.

Real vegetables, these—not those flavorless supermarket things masquerading as wholesome food. You only need bite into a just-picked backyard tomato to know what you’ve been missing all those months following the end of last year’s harvest.

Apples, too, are turning ripe—at least the first of the thin-skinned late-summer varieties.

The other evening I stopped by a favorite tree located in a tangled field near the end of a weedy lane. As I exited my vehicle, four whitetails bounded off. And in the hundred feet between the tree and the road, I flushed two cottontails.

Fellow apple foragers. But no matter. The big tree had plenty of ripe reddish-yellow fruit to go around.

I’m pretty sure the apples are Gravensteins—an old-fashioned variety, thought to have originated in either Russia or Italy and brought to the United States in the late 1700s. Sweet and tart, a dandy eating apple when picked early in the season.

Apples are one of my favorite foods. During years of backroad and backcountry rambles, I’ve noted and mentally filed away the exact location of secluded and forgotten apple trees the same way a prospector catalogs abandoned mine tailings, or a bass fisherman memorizes hidden ponds. I do the same thing with pawpaws, wild pears, persimmons and blackberry patches.

Once the apple season begins in August, and as it continues on through September and into the latter weeks of October—or, weather permitting, perhaps even into the middle of November—I know precisely where to head in a dozen counties whenever I feel the overpowering urge to taste a wild, old-timey apple.

Those back-forty Gravensteins are just the first of many upcoming encounters. My annual apple-fest will feature such seldom-tasted antique varieties as Haralson, Holstein, Fallawater, Pippin, Ben Davis, Nonesuch, Northern Spy, plus two coveted trees which serve up Wolf Rivers.

You can’t buy these apples at the big-box grocery, and only rarely at a roadside stand. But the sharp-eyed backcountry rambler with a discerning palate and a forager’s eye can still stumble upon them, and a dozen similar varieties of savory “lost” apples. Forgotten treasurers hanging on trees located in some weedy corner of an abandoned farm field, or struggling for sunlight amongst some overgrown hillside site where an old home now slowly crumbles back into the earth.

As is the case when comparing home-grown tomatoes to their supermarket counterparts, after the first bite you realize the price of progress and ready supermarket availability—apple-wise, it’s another instance where consumers have been sorely shortchanged in taste. The difference between a commercial apple grown strictly for eye-appeal and shipping qualities, versus, say a gnarled and bent old tree loaded with rather unlovely Ashmeade’s Kernels, is the difference between fancy looks and sublime flavor.

Of course, this is not a problem for the incorrigible forager with a long list of secret trees. Perhaps a notion worth your further contemplation on this betwixt and between time, as summer whirls and sways, dancing along through its final fling, while autumn looms ever closer.

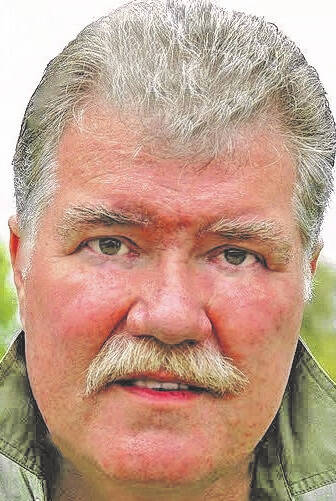

Reach Jim McGuire at [email protected].