On a recent morning, I glanced out my deskside window and did a startled double-take.

A jaunty bluebird was busily helping himself from the nearby feeder! In mid-winter!

Yup…a sure enough bluebird!

The January sky was a dingy gray, thickly overcast, and under its dim, cold pall, the stretch of Stillwater River flowing past our cottage was opaque—a dirty green-brown color of old, long-neglected pewter.

Snow covered the ground and gravel bars, as well as the deck and railing beneath the wire basket holding the usual proffered mix of sunflower seeds and cracked corn.

According to the weather station’s readout, it was a bone-numbing 5˚F outside—but felt way worse if you factored in the wind chill. I’d been doing my duty with the dog a half-hour earlier and had no doubt whatsoever as to the thermometer’s accuracy.

All told, definitely not a morning when you’d expect to see a bluebird—neither the season nor the place.

Yet, there it was, six feet beyond the window glass, a handsome male bluebird.

I recognized it as a male given the bird’s brilliant royal blue back and head, and warm, rusty-red breast. Female eastern bluebirds typically sport a similar feathered dress, albeit less colorful and saturated; they’re more subdued, grayer, rather washed out and faded.

That plumage distinction between the sexes holds true year-round—and while I don’t often see bluebirds during a typical Ohio winter, it’s still pretty easy to tell. Too, following their late-fall molting, the birds are now wearing a new set of feathers—bright, bold, and even more vibrantly colorful.

Bluebirds witnessed in any season are simply dazzling feathered jewels!

I should also say that seeing bluebirds hereabouts during the winter months really isn’t all that uncommon. While various ornithological maps disagree slightly in their seasonal range demarcations, our area of the Buckeye State is on the northern edge of the species’ year-round province. That means some of our local spring-through-autumn bluebirds will migrate, while others will decide to stay put and tough it out through winter.

Food availability is almost always the deciding factor as to whether or not a species needs to migrate elsewhere to survive winter’s harsh conditions.

Most of the year—spring through autumn—bluebirds are predominately insectivores—heavy bug eaters. They also dine on a fair amount of seeds, nuts, wild fruits and berries. However, come winter, with their preferred food now unavailable, they have to switch to pure vegetarianism, foraging harder over a wider range, relying on whatever seeds and berries and similar tidbits they can find.

Cedar berries are the first item that comes to mind as one I’ve regularly noticed winter bluebirds feeding upon.

It’s doubtless their winter need to range farther that annually brings an occasional bluebird to my feeders. While I presume they might also find the occasional wizened fox grape, or, more likely, juniper berries or maybe rose hips—I’ve never actually observed them working either of these.

Because I live directly adjacent to a fair-sized stream, in what amounts to a riverine woodland heavy in sycamore, hackberry, willow, boxelder, plus a dozen similar species, this is decidedly not preferred bluebird habitat. Even my scrap of scraggy grass which I call a yard is spattered with trees and bushes.

Bluebirds prefer semi-open lands—grassy edges, meadows, grassland and prairie borders, old fields, farm lanes, the wide fence rows shoulders and along country roads.

During the spring-through autumn period, throughout the almost two decades we’ve lived here, I’ve seen maybe a dozen bluebirds total hereabouts. And that might be overstating their collective number. However, I always see a few bluebirds during the winter. Never more than one or two at a time—but the birds show up regularly, every winter. And they’re likely bluebirds roaming far and wide in search of a meal.

Some folks, with bluebirds in mind, make mealworms a part of their feeder mix. Others cut up bits of fruit or sprinkle raisins and dried cranberries. Peanut butter and suet are also good.

But I think you have to be a bit closer to good warmer-months habitat to count on seeing many bluebirds showing up at your feeders during the winter—even if you provide these treats. T

he few bluebirds I see annually are probably the more desperate, hungrier birds, willing to search for food far beyond their home territory.

On the other hand, if you know where to look, it’s not too difficult a task to go on a January or February ramble and spot a few mid-winter bluebirds.

For example, there’s a back-in corner in the park up the road where a small flock of bluebirds likes to cluster every winter.

It’s a pretty confined area, and I never see them in this particular place during the warmer months. But from December to mid-March, they’re almost always hanging around this rather restricted spot.

Why? I have no idea. I simply don’t understand the appeal. Cover? Food? Environmental protection or comfort? To me, it seems no different than other similar patches nearby. Yet something—some factor—obviously holds a strong and enduring seasonal attraction.

My recent bluebird picked and poked around the feeder for maybe half an hour. Then he took off…and just that quick, my morning’s magical interlude was over.

I won’t likely see any of his kith or kin again until spring.

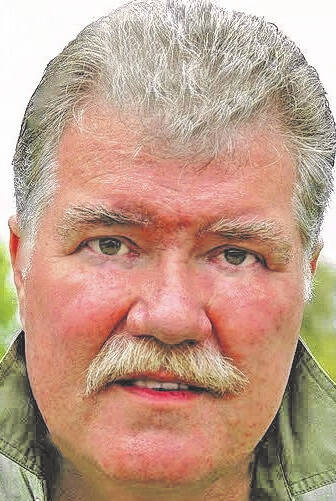

Reach Jim McGuire at [email protected].